Analysis of CO2 Plume Dispersion Modeling for One Earth Pipeline in Illinois

One Earth proposed 7.34-mile CO2 pipeline route in Illinois

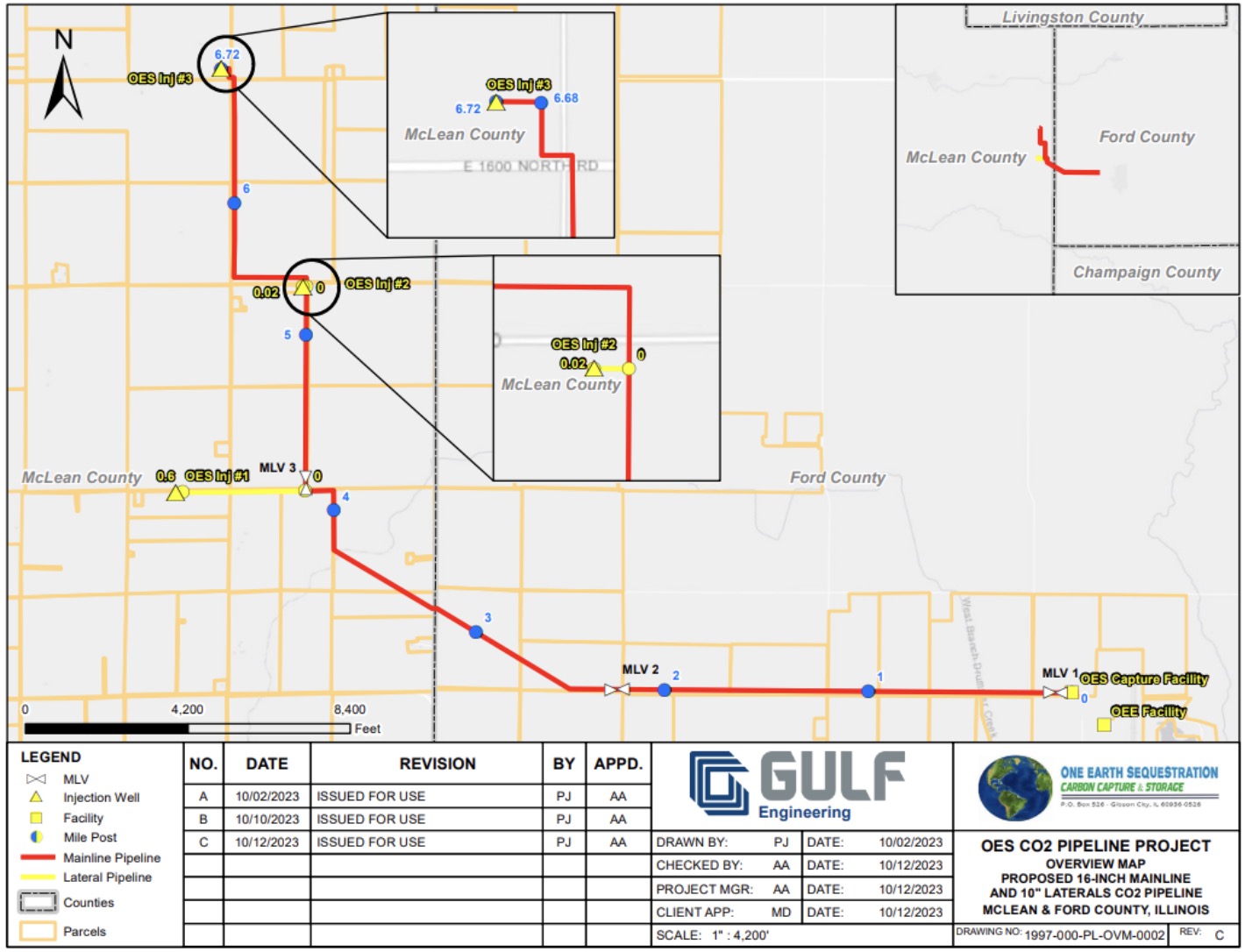

In Illinois, One Earth Energy, LLC is seeking permits from the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC) and community support for its plan to build a 7.34-mile CO2 pipeline to sequester carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the 150-million-gallon ethanol facility operated by One Earth in Gibson City (Ford County) to an injection site in McLean County.

The One Earth ethanol plant produces approximately 420,000 metric tons of CO2 annually, but the company is proposing a much larger 4.5 million metric ton-capacity pipeline so it can also potentially serve “additional third-party customers.”

Just like it has previously recommended rejection of CO2 pipeline permits for projects proposed by the now-defunct Navigator CO2 Ventures, and Wolf Carbon Solutions, the Illinois Commerce Commission staff has recommended a rejection of One Earth’s permit application as well, citing safety issues and lack of adequate federal or state safety regulations.

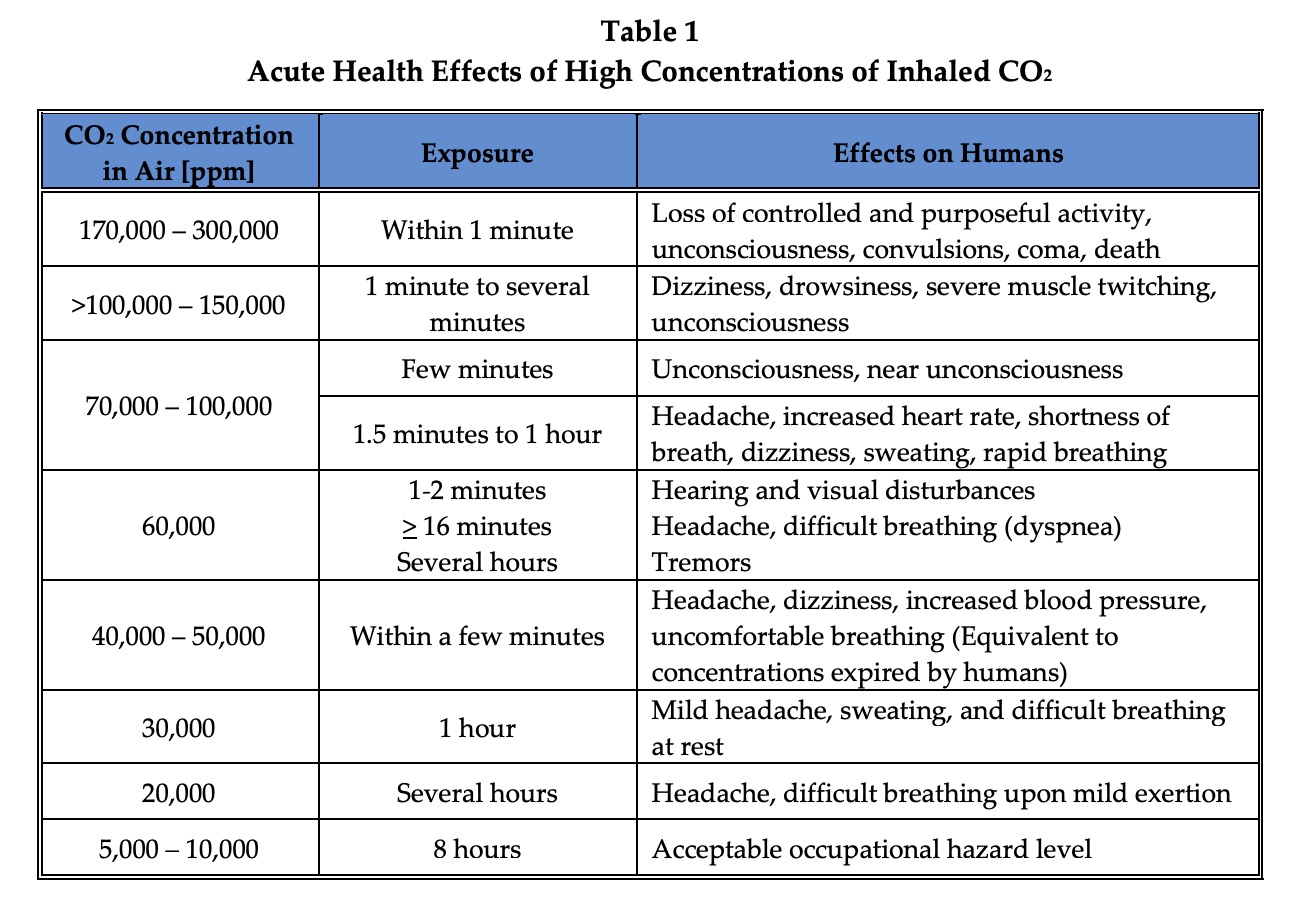

Among the major concerns with CO2 pipelines are potential leaks of the gas which displaces oxygen and can cause immediate health impacts ranging from nausea to unconsciousness, and prevent combustion engines from functioning and first responders without electric vehicles from helping victims.

Modeling exists to predict where and how far and at what concentrations the escaped CO2 may travel, but pipeline companies have argued this data should be kept secret from the general public. When pressured by state agencies, pipeline operators have disclosed “plume” model data to first responders and some local authorities, but so far have refused to share any complete data or especially “worst-case scenario” data publicly.

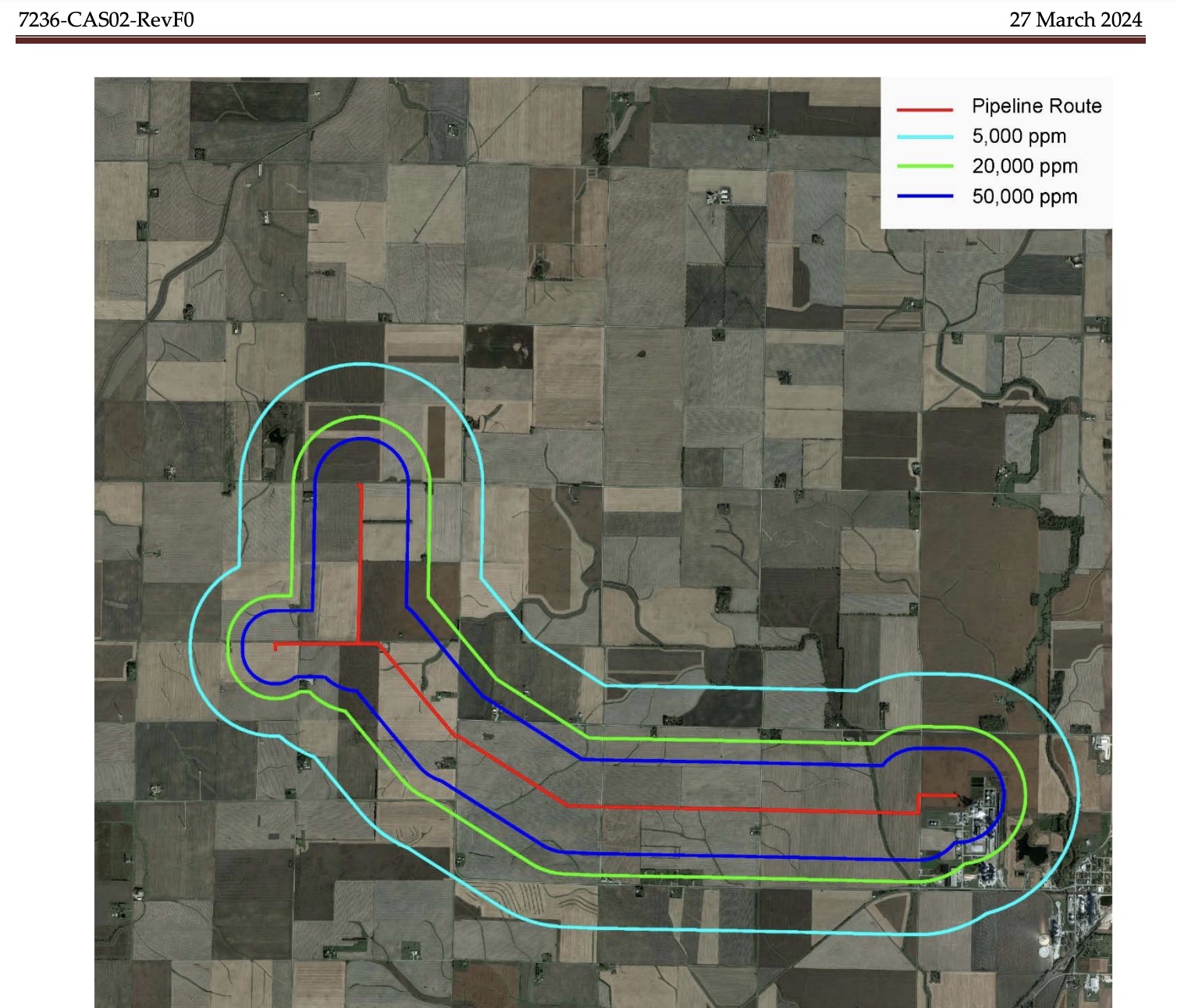

As part of its application to the Illinois Commerce Commission, One Earth included a limited CO2 pipeline leak plume dispersion model, that is publicly available via the ICC’s docket:

Poor weather condition (low winds) CO2 pipeline leak plume dispersion modeling filed by One Earth Energy to the Illinois Commerce Commission

The first thing that stands out in One Earth’s plume dispersion model: “rupture events were assumed to be detected, valves shut, and pipeline flow terminated within 5 minutes.”

Five minutes, from the presumably instantaneous detection at the exact time of the rupture by sensors or a control room operator, to the time the valve is completely shut off and flow of CO2 stopped.

And while One Earth’s claim of a five-minute shutoff time for a CO2 pipeline leak might sound impressive, Summit Carbon Solutions, developer of a proposed five-state, 2,400-mile CO2 pipeline across the Midwest claims it will be able to detect and shutdown valves to stop the CO2 flow just two minutes* after a leak incident.

(*North Dakota Public Service Commission, Case No. PU-22-391 Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order, page 10, “Additional Measures to Mitigate Impact,” #38)

These claims do not mesh with reality and recorded history, where pipeline leaks often go undetected until discovered by a neighbor — as was the case on April 3, when a neighbor first reported a leak on operator Exxon/Denbury’s “Green” CO2 pipeline near Sulphur, La.

Not only did the sensors and control room not detect this CO2 pipeline leak of 2,548 barrels (107,016 gallons), but the Lake Charles Pumping Station where it occurred was unmanned at the time of incident, the neighbor was unable to reach Denbury to report the CO2 leak approaching her home, and after Exxon was notified — it took more than 2 hours for them to travel from Beaumont, Texas to the incident site in Louisiana and completely shut off the flow of CO2. A shelter-in-place order was issued for a quarter-mile radius of the CO2 pipeline pump station for a period of over two hours during the incident.

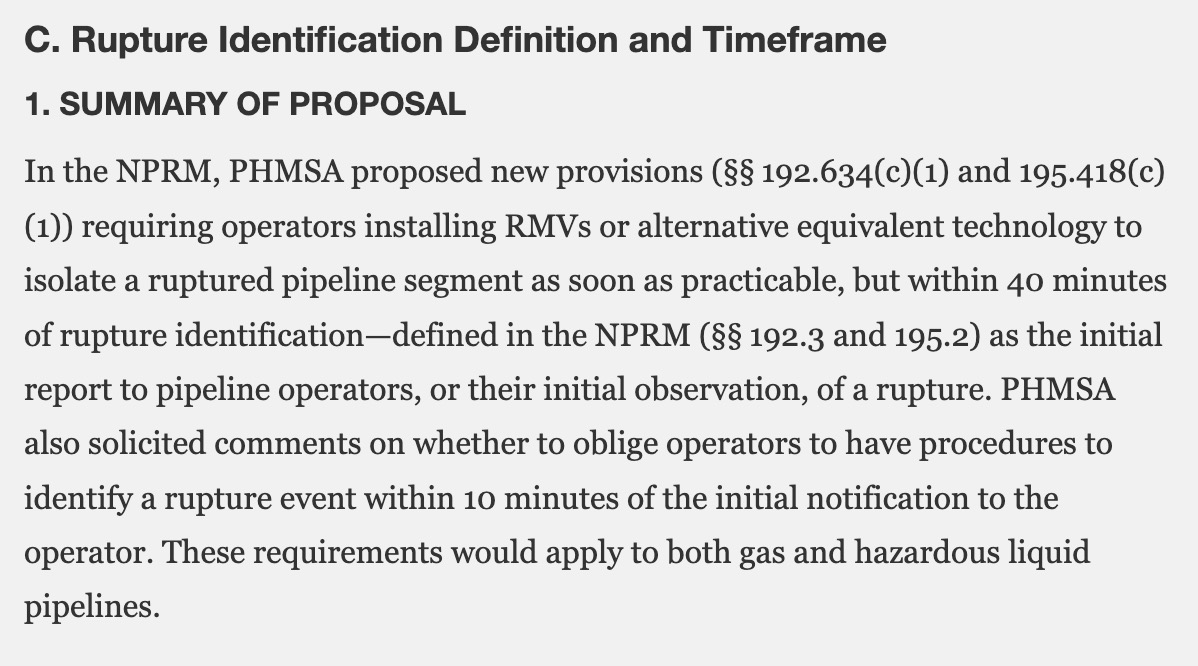

A new rule related to Requirement of Valve Installation and Minimum Rupture Detection Standards was finalized by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration on April 8, 2022.

During the public comment period, the industry group Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA) and gas pipeline operator Northern Natural Gas argued that the requirement time for closing a valve be a much longer 60-minute or 40-minute window, compared with the 2- or 5-minute shutdown time estimates made by Summit and One Earth. The industry group INGAA argues that even a 60-minutes timeframe is too short for them to respond to in areas outside of class 3 and 4 locations (less populated areas), and that rural topography and an incident during winter months would delay this total response time from the moment an incident happens until complete valve shutdown beyond one hour:

“Northern Natural Gas Company asserted that the requirement for closing a valve to isolate a rupture within 40 minutes does not allow adequate time for the pipeline controller to evaluate the nature of the pressure change, determine if there is an emergency, or identify the actions needed to mitigate the emergency. Therefore, Northern Natural Gas Company recommended PHMSA change the rupture identification and valve shut-off period to 60 minutes total. It stated that a 40-minute valve closure requirement could result in too-rapid decisions to shut-in pipeline segments, causing unnecessary outages, unanticipated pressure changes, and potential damage to the pipeline system.”

“INGAA et al. recommended that PHMSA apply the 40-minute valve closure time only to pipelines in HCAs and Class 3 and Class 4 locations to allow more flexibility in remote areas, noting specifically that achieving valve closure within 40 minutes is typically more challenging in remote areas. They noted that operators are likely to consider the use of manual valves in remote areas because an ASV, RCV, or equivalent technology would be economically, technically, or operationally infeasible, as it can be difficult to provide power or communications to automated valves in remote areas. INGAA et al., further noted that pipelines traverse a multitude of geographies, including locations that cannot safely be reached within 40 minutes, particularly during winter months.”

“However, PHMSA remains concerned that, in the absence of a minimum rupture identification time interval, a scenario similar to those that played out during the Marshall, MI, and San Bruno, CA rupture events—in which there were extended delays in rupture identification and response despite multiple indicia of a potential rupture—could happen again… PHMSA further notes that any risks to the public and the environment arising from delays in rupture identification for operators installing RMVs under this final rule would be further reduced by each of (1) language in §§ 192.615 and 195.402 requiring operators to ensure that their protocols identify ruptures “as soon as practicable” and (2) language at §§ 192.636 and 195.419 imposing demanding timelines—“as soon as practicable,” but not to exceed 30 minutes from rupture identification—for operation of RMVs following rupture identification.

The Pipeline Safety Trust told us they “believe generally that shutting down pipe quickly is likely the safest option in the vast majority of scenarios, and that valves requiring manual closure allow uncontrolled releases to continue for far too long.”

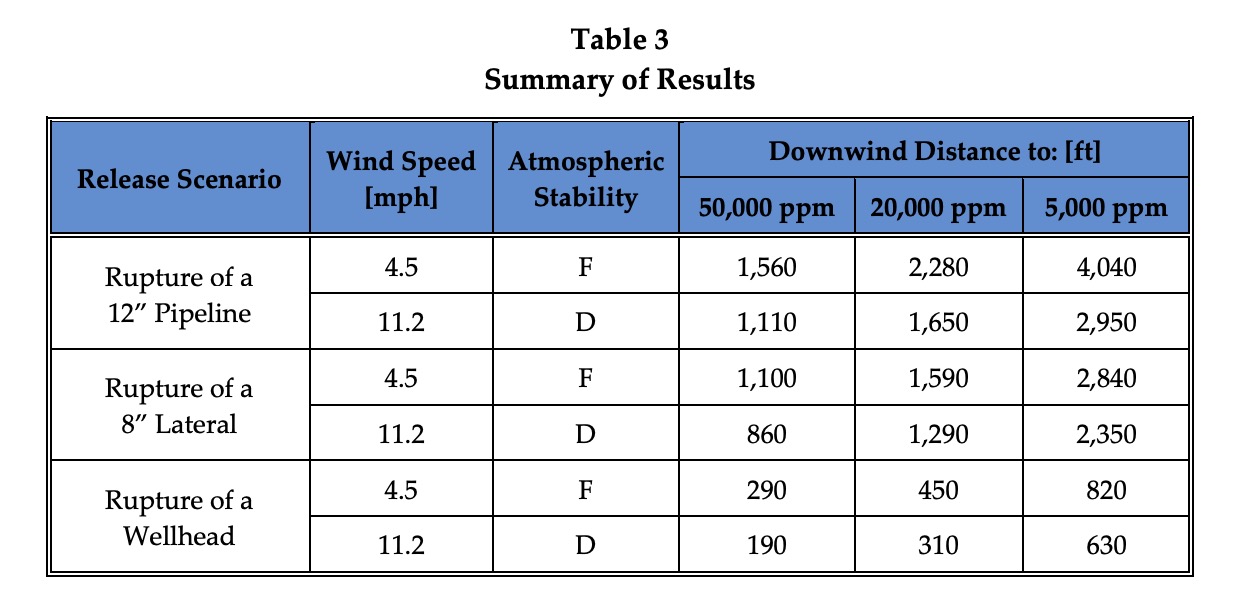

One Earth’s calculations are based on only allowing CO2 to escape for 5 minutes, versus real-world scenarios where experience shows leaks generally persist for at least 30-60 minutes, and sometimes 2.5 hours like the Exxon leak in Sulphur, La. last month or four hours during the Satartia, MS Denbury pipe leak incident in 2020, it’s impossible to rely on One Earth’s provided data to calculate risks to nearby lives and communities from its proposed CO2 pipeline.

The One Earth CO2 pipeline leak plume dispersion modeling is also based on several other pre-set variables and assumptions about the effects of CO2 on health based on the concentration present in the air, which would not be accurate if based on faulty assumptions of the time it would take to stop the flow of CO2 after a rupture. Fatal concentrations would exist close to a rupture, but the company has not provided the fatality distance.

One Earth ICC permit application

One Earth ICC permit application

Pipeline Safety Trust Comments to PHMSA (April 2020)

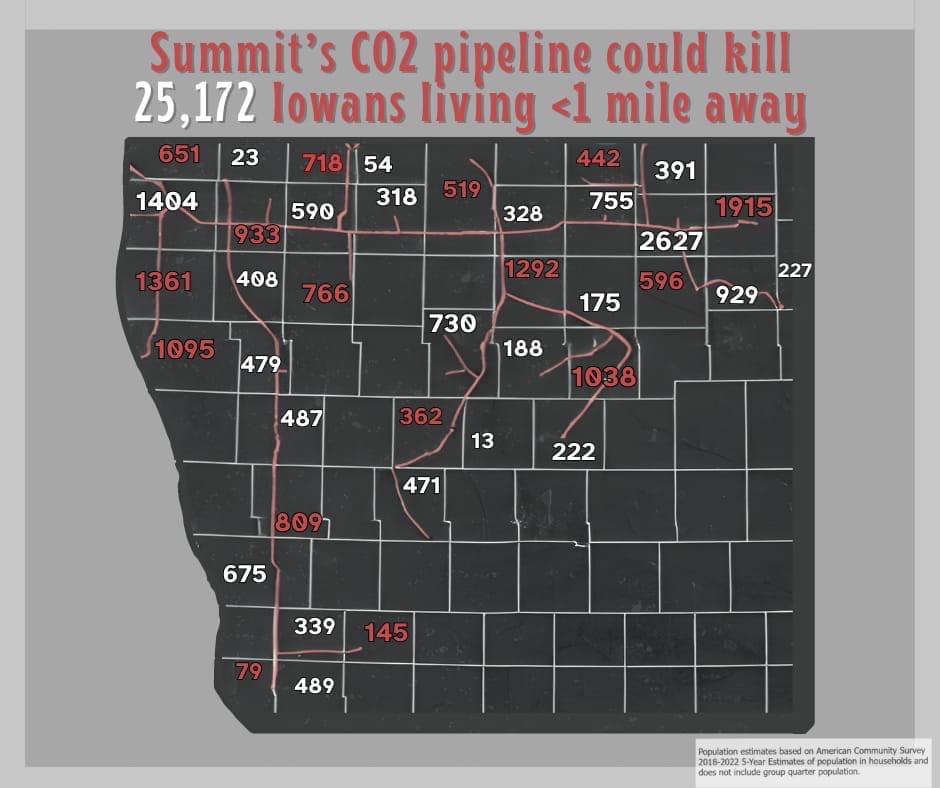

PHMSA-2013-0255-0023_attachment_1People in the Plume: Summit CO2 Pipeline Iowa Populations Within 1 Mile by County

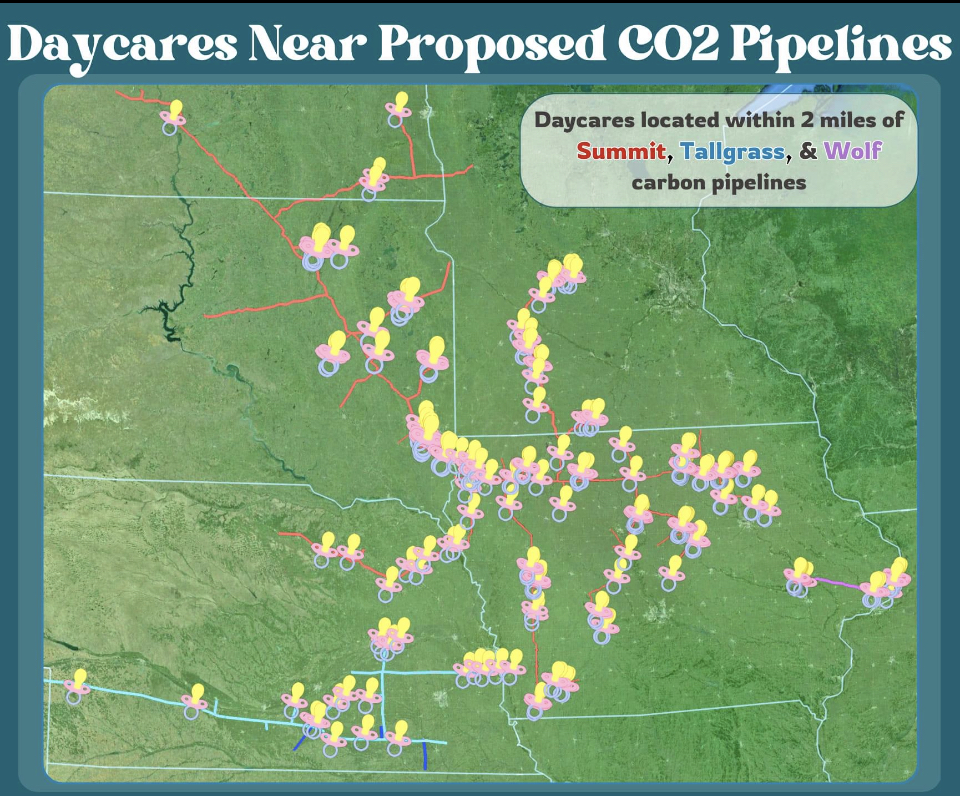

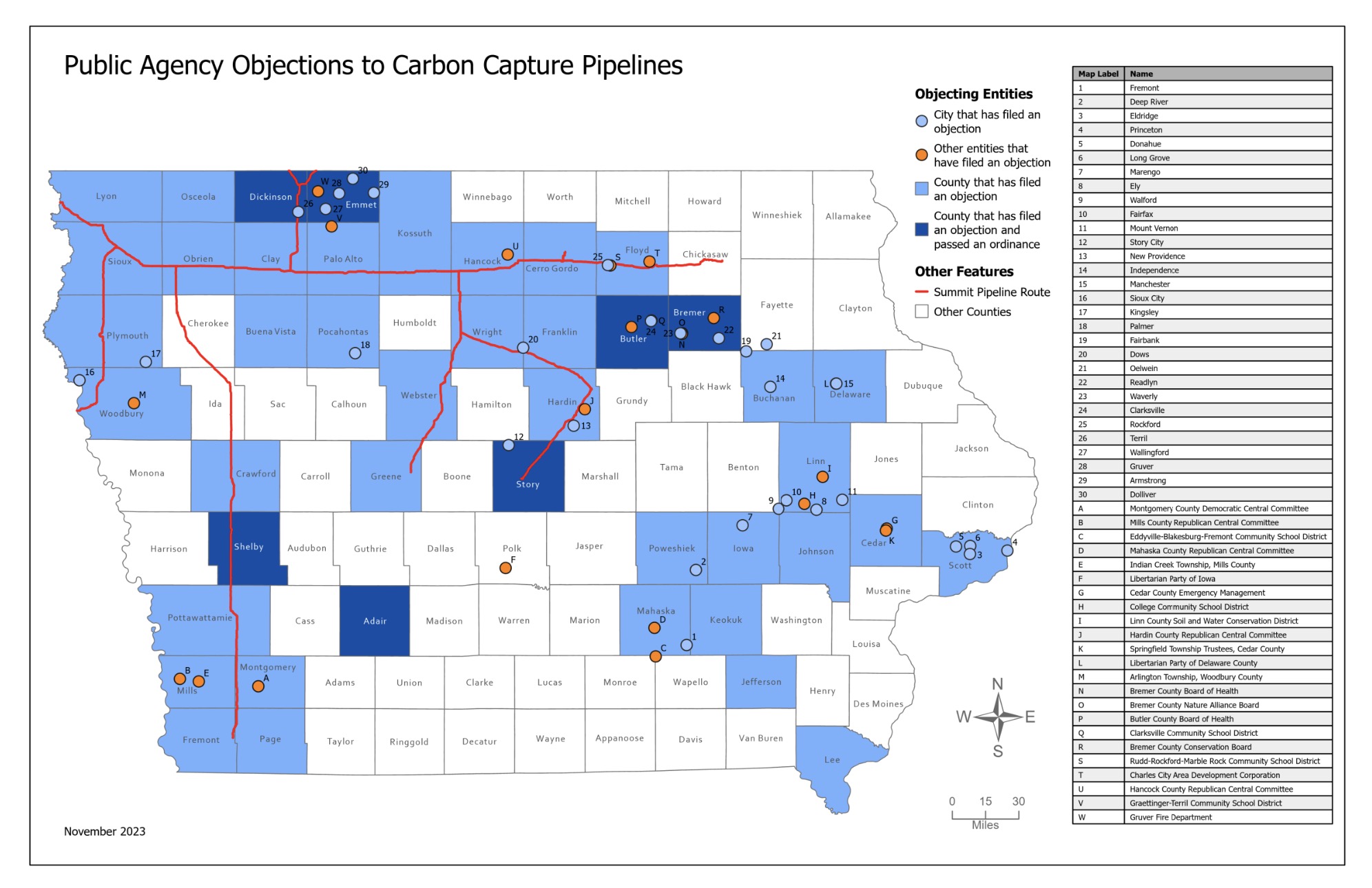

Iowa Public Agency Objections to CO2 Pipelines for CCS (Map by Jason Howard)